Science fiction celebrates all manner of things; one of them is what some people might call “making hard decisions” and other people call “needless cruelty driven by contrived and arbitrary worldbuilding chosen to facilitate facile philosophical positions.” Tomato, tomato.

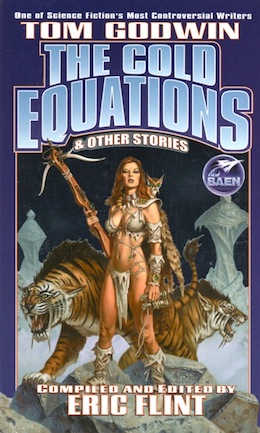

Few works exemplify this as perfectly as Tom Godwin’s classic tale “The Cold Equations.” The story is perfectly spherical nonsense, absurd from any direction one looks at it. Because it provides an apparent justification for doing terrible things in the name of necessity, a lot of fans and editors love it. Just look at how often it has been anthologized.

I suppose if I don’t put in a spoiler warning for a 65-year-old story, someone somewhere will complain. So here it is in bold print…

[Spoilers below. And also murderous jerks.]

I am totally going to reveal in the text below that the adorable young girl in the story is executed because she stows away on a space ship run by an organization whose motto appears to be “Depraved Negligence.”

A quick synopsis for those of you who don’t want to spend the time to read the story, which is available here: a single-crew emergency dispatch ship (EDS) bearing much-needed medical supplies is launched towards colony world Woden. After launch, pilot Barton discovers too late that Marilyn Lee Cross has stowed away on the vessel. The regulations are very clear:

Paragraph L, Section 8, of Interstellar Regulations: “Any stowaway discovered in an EDS shall be jettisoned immediately following discovery.”

There is no room for mercy because the ship has only enough fuel to reach Woden (assuming that no extra mass is added to ship). After a certain amount of dither, poor naive Marilyn is spaced. The Cold Equations always win.

Some critics have gone after this story on plausibility grounds—what sort of idiots would design a system with no redundancy or margin of error?—but, hey, SF is filled with set-ups that are exquisitely designed to tell the story the author wants to tell. It’s traditional. So, I’ll refrain from criticizing “The Cold Equations” for its bold spaceship design. If we allow Niven’s poorly programmed robot probes or Spinrad’s orgasm-fuelled FTL drive, we’ve got to allow a situation where ships are used at the ragged edge of their performance capacity .

BUT…let’s consider another aspect of worldbuilding. How is the ship protected against stowaways?

As far as I can tell from the text, the sole security measures used prior to dispatching EDSes is a sign that reads “UNAUTHORIZED PERSONNEL KEEP OUT!” and the vague hope that if someone does try to sneak on board, someone or other will notice. Marilyn says, “I just sort of walked in when no one was looking my way.”

The only lock mentioned is the airlock through which Marilyn exits the story.

Digression time:

I once made the mistake of musing while boarding a plane how odd it was that given my anxiety about being in vehicles controlled by other people (a side effect of the event that led to me spending a year legally dead), flying didn’t particularly stress me. Cue sudden onset airplane phobia. One of the ways I mitigate this is by watching episodes after episode of the airplane crash forensic show, Mayday. I find the recurring theme, that airplane mishaps almost never have a single cause, reassuring. At least in theory.

It’s a shame that Mayday devotes so little of its time to dissecting old science fiction stories. Trust me, a Mayday-style post-flight analysis of Marilyn’s murder would be hilarious. The spaceline authorities would explain that they’ve been killing people for years without anyone complaining. They would then admit that although people stowing away on emergency craft is a common enough problem that there are draconian regulations in place to deal with stowaways, it’s apparently never occurred to anyone to include searching for stowaways in the pre-flight check list. Or even to install locks anywhere.

Now, as for the characters in the story…if they hate ejecting people into space, why haven’t they installed their own locks? Why haven’t they put a stowaway check in the departure checklist?

But of course, the point of the story, as determined by the author and his editor, John W. Campbell, Jr., is to underline a moral: the universe doesn’t care about human feelings. Natural law dictates that hard men must make hard choices.

What the story actually says is that lousy procedures kill.

Just another instance of humans looking for justifications to be beastly to each other.

Still, there is a story that makes the point Godwin and Campbell thought they were making (i.e., nature is merciless). This story is, of course, Jack London’s “To Build a Fire,” in which an arrogant man’s ignorance of Yukon winter conditions leads to his (entirely avoidable, if he had been a person who would listen to advice) death. Anthologize that!

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.